What a future without browser cookies looks like

Most online users have experienced it. You do an online search for healthcare purposes, travel information, or something to buy and soon you’re being bombarded with emails and targeted online ads for everything related to your search. That’s because browser cookies were tracking you as you performed your searches; they identified you and your activity.

Over the past few years, the online advertising industry has been undergoing a sea change as regulators restricted how cookies can be used and browser providers moved away from their use in response to consumer outcries over privacy.

“They often feel surveilled; some even find it ‘creepy’ that a website can show them ads related to their behavior elsewhere,” according to a recent study by the HEC Paris Business School.

Cookies often ingest and retain sensitive consumer information including login credentials, personally identifiable information, and browsing history. As a result, the move away from cookies should help reduce some cybersecurity risks.

“However individuals should remain vigilant, as hackers are always one step ahead,” said Roger Beharry Lall, research director for IDC’s Advertising Technologies and SMB Marketing Applications practice.

Advertisers are already working on new consumer-tracking technology to replace cookies, he said.

“In the short term, there will be some disruption with advertisers struggling to market themselves effectively,” Lall said. “This may seem good for consumers who are ‘cookie free.’ However, there will likely just be more irrelevant ads flooding the media trying to find an audience. So, it’s a bit of a double-edged sword.”

As far back as 2019, Google was telling users it planned to limit third-party cookies and would phase them out in Chrome and other Chromium open-source browsers by 2022. In 2022, Google pushed its cookie elimination plans back to 2023. And last year, it pushed back the plans again — to the second half of 2024.

Google

GoogleGoogle also scrapped its original plans in favor of a less ambitious strategy.

“While they have made public statements about depreciation, it wouldn’t surprise me at all if depreciation gets pushed well into 2025,” Lall said. “They’ve delayed many times before, so they haven’t earned a lot of trust in this regard.”

While rivals are far ahead of Google and Chrome in blocking or limiting third-party cookies, Google’s overwhelming dominance of the market (64% of worldwide browser market share) will undoubtedly have a far greater impact — if the company makes good on its promises.

Its rivals have moved faster in addressing the issue. Mozilla’s Firefox began blocking third-party cookies in 2019. Apple’s Safari 13.1 began blocking all third-party cookies by default in 2020.

Microsoft has taken a different approach with its Edge browser, which offers an all-or-nothing option for allowing or denying third-party cookies. The default setting allows cookies. “You can let all websites create cookies, or no websites create cookies,” Microsoft’s policy explains. “You can’t use this policy to enable cookies from specific websites.”

A Microsoft spokesperson yesterday argued that, “Microsoft Edge already provides customers with built-in tracking prevention and additional settings to block [third-party] cookies if they choose. The industry is on a journey to create new privacy preserving web standards that don’t rely on [third-party] cookies. As this work evolves, we will continue to support solutions that maintain consumer choice and control while balancing a healthy ecosystem for all.”

Microsoft also pledged to detail any future changes to the Edge browser that might affect website compatibility.

As for Google, in January, it began testing a version of Chrome without cookies for just 1% of users. The program, called Tracking Protection, is part of a larger effort known as the Privacy Sandbox Initiative — an effort to reduce cross-site and cross-app tracking.

“The countdown to the planned deprecation of third-party cookies is in full effect,” Anthony Chavez, Google’s vice president for Privacy Sandbox said in a September blog post. “We look forward to continuing to partner with the industry on this transition, including supporting the adoption of Privacy Sandbox APIs and evaluating their effectiveness through scaled testing

Privacy Sandbox APIs are not intended to be direct, one-to-one replacements for all third-party cookie-based use cases or to be a standalone ad tech solution, according to Victor Wong, senior director of product management for Privacy Sandbox.

“Instead, they are designed to provide foundational elements that support core business objectives for marketers and publishers (like driving online sales and serving relevant ads), without cross-site identifiers,” Wong said in a Jan. 10 blog post.

The current Privacy Sandbox APIs — generally available in Chrome since September — “are ready to carry the ecosystem into a more private future,” Wong said.

Developers can use Privacy Sandbox APIs alongside other technologies and inputs to achieve outcomes similar to those of cookies, according to Google.

Because the Sandbox APIs, by design, don’t re-create the same functionality of third-party cookies and other cross-site identifiers, developers might need to redesign how their existing products work, according to Google.

“For example, running an ad auction on-device means that previously server-only functionality will now interact with ad tech code running in a browser,” Wong said. “And certain capabilities that relied on third-party cookies, like audiences based on profiles of user activity across websites, will not be possible to directly replicate using the Privacy Sandbox.”

According to Mike Froggatt, a senior director analyst at Gartner, there is no one-to-one replacement for cookies across the advertising industry. There are, however, several device-level identifiers for advertisers (IDFA) options, including ones from Apple and walled gardens like Google’s and Meta’s, as well as third-party tech proposals such as UID2.

“However, these are typically closed systems that restrict access and only report or share data in aggregate,” Froggatt said. “Even Google’s Privacy Sandbox, which proposes on-browser auctions, only shares data after a certain threshold is hit, and even then, will add ‘noise’ or additional data to mask any individual identifiers.”

Details on the Privacy Sandbox seem to be “evolving,” IDC’s Lall said, which “is reasonable since the environment is changing rapidly.

“It won’t be a cookie replacement and it will be safer (limited information sets, more transparency, stronger cross-site limitations, etc.), but a lot of the advertising details are unclear,” Lall said.

Contextual targeting of consumers

For some time now, vendors have leveraged “contextual targeting” based on items such as viewing platform, industry, interests, related ads, keywords, and other parameters. Basically, the tools allow advertisers to display relevant ads based on a website’s content rather than using data about the visitor.

“These solutions are not cookie based and don’t identify an individual per se, but rather seek to provide advertisers with audiences based on real-time behaviors,” Lall said.

Contextual targeting can actually provide do a better job of spurring consumer purchases than cookies, according to Lall. Typically, vendors will provide pre-segmented groups based on contextual markers (e.g. back-to-school moms, valentine males).

Vendors have also been developing “ID resolution” tools that help them identify anonymous website viewers based on interactions using deterministic or probalistic approaches. At first, a consumer browsing a website would be anonymous. But after interacting with the site, and responding to question-and-answer forms, the system can backtrack and identify the user and their entire site-related browsing history.

“While the resulting ads may feel invasive due to their accuracy, they aren’t invading privacy because they are targeted to a person’s behaviors vs. targeting the person,” Lall said.

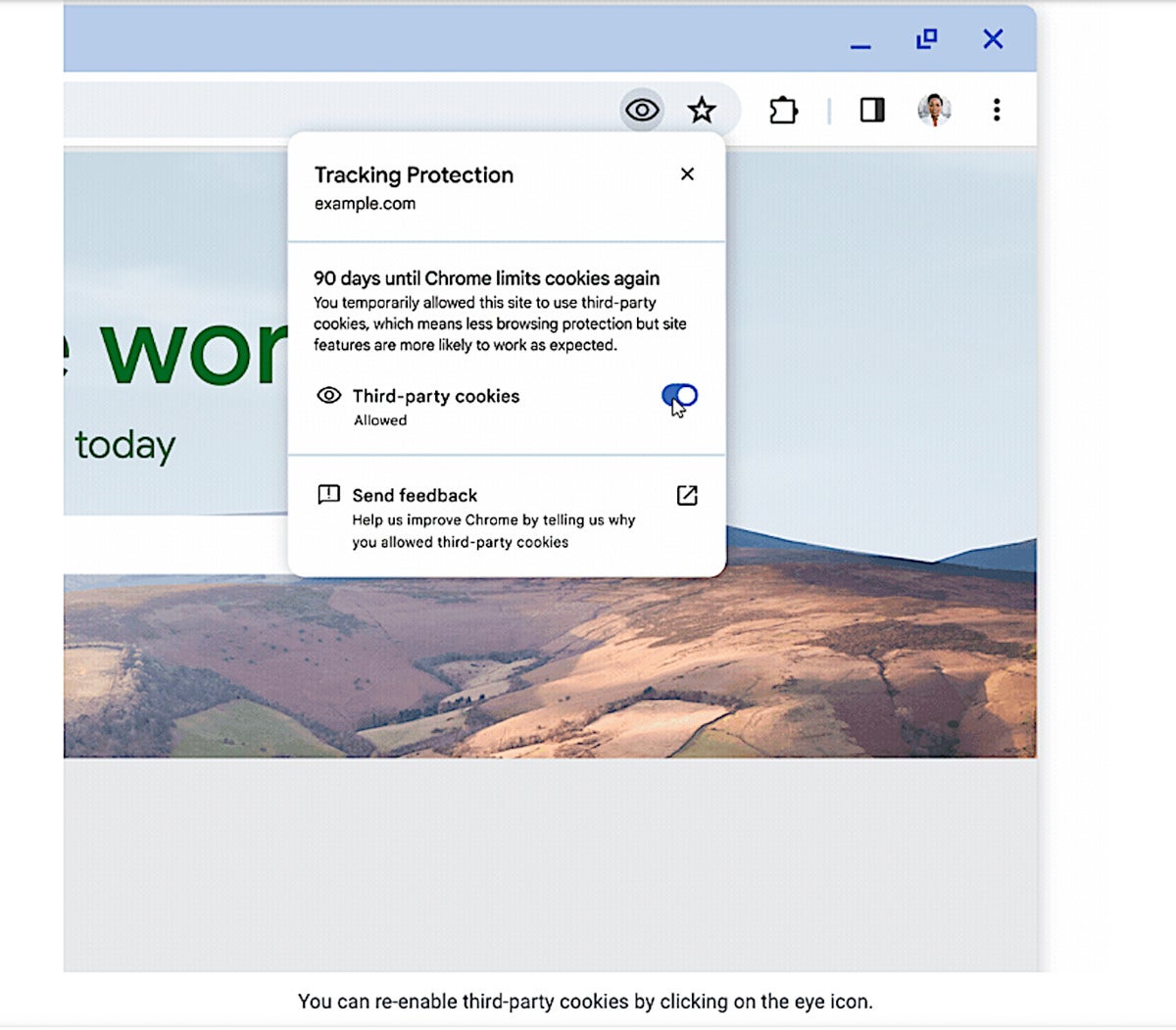

Google

GoogleTracking protection restricts third-party cookies by default, limiting the ability to track users across different websites. Users can choose to turn to function off, too. (Google claims the effort is to increase privacy across the web.)

While there are multiple reasons for Google’s slow response to other providers, the most relevant is that its Sandbox initiative is being built under the supervision of the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), according to Froggatt.

Google also still receives a healthy chunk of revenue from its display ads, Froggatt said.

“While not completely reliant on third-party cookies for targeting and measurement, they are a signal used to increase the value of media that they sell on behalf of publisher/media supply partners with data requested by agencies and advertisers,” Froggatt said.

Google will likely continue tracking consumers solely through its own tools, “so, it remains a walled garden,” Lall said. “The more Google acts in a monopolistic/closed manner, the more regulators will need to engage.

“You still won’t be able to connect the dots from your ‘privacy sandbox API,’ to a ‘known individual’ in this cookieless scenario. As such, you’ll need ID resolution or other first-party data solutions to move from ‘anonymous user interested in XYZ’ to ‘Jane Smith purchased XYZ,’” Lall said.

When it comes to protecting consumer privacy, cookies alone weren’t particularly vulnerable to hacks and they did provide users with some control over their data, according to Froggatt.

“They actually grant quite a bit of control to users via clearing browser caches, blockers, especially compared to device IDs and IP address,” he said.

In some ways, newer methods for tracking consumer trends shift the responsibility from the individual to the companies that operate those closed systems, Froggatt said.

“…Looking at the history of massive data breaches, [that] doesn’t bode well for users,” Froggatt said. “At least data used by advertisers and ad tech shouldn’t include much beyond demographic data, browsing/purchase history and maybe some location data, versus credit card, password and other data leaked in the past.”

Efforts to protect consumer privacy online growing

In November, the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office warned the nation’s top website providers they must comply with data protection laws that require them to allow users to “Reject All” or “Accept All” advertising cookies. Websites can still display advertisements when users reject all tracking, but must not tailor them to the person browsing.

“Our research shows that many people are concerned about companies using their personal information to target them with ads without their consent,” Stephen Almond, ICO executive director of regulatory risk, said in a statement.

“Gambling addicts may be targeted with betting offers based on their browsing record, women may be targeted with distressing baby adverts shortly after miscarriage and someone exploring their sexuality may be presented with ads that disclose their sexual orientation,” Almond said.

Along with other academics, HEC Paris Marketing Professor Klaus Miller completed a study last year suggesting that the proposed cookie restrictions could lead to losses in ad revenue. In the US, online advertising revenue amounted to $209.7 billion in 2022.

While there are some government efforts under way to better secure consumer data from invasive cookies and other tracking software, at least at the federal level, the US isn’t expected to make waves.

“When it comes to the US, it is really down to the states; the prospects of a national digital privacy act are nearly nil,” Froggett said.

Restrictions on cookies, however, might be ineffective in the long run anyway. That’s because the majority of browser users (72%) delete their cookies within a year; up to 85% delete them within two years.

Assuming Google follows through on its cookie deprecation (with full depreciation by the end of 2024), “it’s unlikely that other countries will pursue regulatory controls,” IDC’s Lall said.

“The wheels are already in motion to remove cookies, so I’m not sure that more regulation will help,” Lall said. “That said, there is an increase in legislation (in the US and everywhere) related to protecting consumers and privacy. This is broader than ‘cookies’ and is meant to establish clear foundations around trust.”