Top web browsers 2020: Chrome becomes third browser ever with more than 70%

Google’s Chrome cracked 70% last month in the browser share sweepstakes, setting another record as it reached a number held by only two other browsers in the history of the web.

According to data published last week by analytics company Net Applications, Chrome’s share during June rose four-tenths of a percentage point to 70.2%. The browser has been on a sixth-month run, adding 3.6 percentage points to its account since January. The only other browser to end the first half of 2020 on a positive note was Opera Software’s Opera, which gained just one-tenth of a point in that time.

More notable was that, by breaking the 70% bar, Chrome became only the third browser to reach such a dominant position, following Netscape Navigator (ancestor of Firefox) in the 1990s and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer in the first decade of this century.

Chrome’s continued climb may not be sustainable over the long run – that would require the extinction of at least one rival – but on a strictly linear basis, the browser’s future looks rosy. Computerworld‘s latest forecast, based on a 12-month average change in share, puts Chrome at 71% by September and beyond 72% by year’s end.

Microsoft’s Edge will be the sole conceivable threat to Chrome’s overwhelming majority, and then only if organizations – businesses and universities in particular – adopt the Chromium-based clone because of its manageability and then users mimic that at-work move on their personal devices after hours.

Edge’s increase: Caused by Chromium or Windows 10?

Microsoft’s two browsers, Edge and IE, combined to post a rare increase in share, upping their combined number one-tenth of a percentage point in June to 12.6%.

The growth was all on Edge, which gained two-tenths of a point to reach 8.1%, a record for the five-year-old browser. Meanwhile, IE lost half as much, slipping another tenth of a point to 4.5%. The phrase, “Two steps forward, one step back,” has become Microsoft’s literal rate of change.

IE’s 4.5% – a record low for the browser veteran this century – transformed into a somewhat better 5.2% when judged against only Windows’ share of all personal computers. (The disparity of shares of all systems versus those running Windows only is due to the latter’s own share – 86.7% in June – falling well short of the 100% an all-PC total represents.)

Computerworld remains convinced that Net Applications’ numbers tell only a partial story; they are unlikely to accurately portray usage inside an enterprise, where a single external IP address may mask multiple internal addresses. It’s more likely that Net Applications undercounts (rather than overcoats) IE. Still, it’s unclear whether Microsoft still sees IE as an important enterprise tool because of the browser’s active use by businesses or because a handful of customers – very large, important customers – demanded continued support.

The IE forecast now envisions the browser’s share plummeting to 1.8% by this time next year, and theoretically evaporating entirely by January 2022. One wonders who, if anyone, will then mourn IE’s passing.

On the other hand, Edge’s June was the seventh straight month of increases. The month pushed the 12-month total to just over 2 percentage points, an increase bested only by the browser’s first year, when it put on approximately 5 points.

Since the end of January – Edge launched in the middle of that month – Edge’s share has climbed by 1.1 percentage points, an increase of almost two-tenths of a point per month.

At first glance, that would seem to validate Microsoft’s decision to “Chromify” Edge by adopting Chromium as its browser’s foundation. Surely that move was responsible for the increase?

Perhaps. But there’s no way to know with certainty.

Although the five months prior to Chromium Edge’s release (September to January) added less to the browser – just seven-tenth of a point – the five months before that (April through August) recorded a just-as-good 1.1 percentage points.

It’s just as reasonable to assume that Edge’s climb – whether old or new Edge – is just as much due to the increase in Windows 10’s share as any change to the browser itself. Since Chromium Edge’s debut, Edge’s share of all Windows 10 browser activity climbed from 12.9% to 13.7%, an eight-tenths of a point boost. In other words, the bulk of Edge’s last-five-months increase 8 out of 11 tenths, or 73%, could just as easily be attributed to Windows 10’s accumulation.

At its current 12-month average, Edge should be in double digits – around 10.1% — by July 2021.

Firefox scratches back some lost share

Things are looking up for Mozilla: June was the third straight month that Firefox held onto or increased its share; the browser ended June at 7.6%, up four-tenths of a point from its April and May 7.2%. At the end of June, Firefox’s share was identical to its end-of-February total.

Even with the increase, Firefox remained in third place behind Edge. (Firefox lost its long-held second spot in March.) The gap between the two shrunk by a tenth of a point to five-tenths of a percentage point. Yet it’s unlikely that Firefox will reclaim the second position as predictions point to a widening difference over the next 12 months.

Computerworld‘s latest forecast continues to predict declines ahead for Mozilla’s browse. Firefox won’t slip below 7% until December (last month’s prognostication indicated that would happen this month) and a year from now will still stand above 6%. Although still discouraging for Firefox fans, the forecast is less dire than previous ones, with just the slightest hint that the decline has eased its pace.

But by those prognoses, the gap between Edge and Firefox will have grown over the next year to nearly 4 percentage points.

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ data, Apple’s Safari shed three-tenths of a point, dropping to 3.6%, its lowest mark since October 2019. Opera software’s Opera remained flat, ending June at 1.1%.

Net Applications calculates share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers used to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm counts visitor sessions to measure browser activity.

Top web browsers, May 2020

Chrome’s share reached a record high in May, the fifth straight month of gains, a run the browser last enjoyed three years ago.

According to data published Monday by California metrics vendor Net Applications, Chrome’s share in May climbed six-tenths of a percentage point to 69.8%. The browser has been on a run of late, with the previous five months – January to May – putting 3.2 points on Chrome’s ledger. The only other browser to post gains during that stretch – Safari – added a mere two-tenths of a point.

To put Chrome’s position into perspective, no browser has had more than Chrome’s current share since December 2008, when Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (IE) held more than 70% even as it was trending down, under assault from Mozilla’s Firefox. (That month, Chrome, which had debuted only months before, accounted for a tiny 1.4% of all browser share.)

May’s addition changed Chrome’s 12-month forecast, which now predicts the browser will reach 70% this month (June) but will need until December to make 71%. If Chrome breaks the 70% bar, it will become only the third browser to do so, following Netscape Navigator (an ancestor of Firefox) and IE.

It’s unclear how much headroom Chrome has – it seems very unlikely that it can duplicate IE’s crushing dominance of, say, 2005, when that browser had close to a 90% share – but it almost certainly can squeeze a few more points out of the competition. IE has points to give up, not many but at least a couple, while Firefox could easily continue its ruinous slide and slough another two or three percentage points.

As Computerworld has said before, the only threat to Chrome in the near term will be Microsoft’s Edge, the Chrome clone.

Firefox hangs in there

For a second straight month, Firefox held onto its share; the browser ended May with 7.2%, losing a statistically insignificant two-hundredths of a point.

May was also the third consecutive month that Firefox sat behind Edge after losing its second-place status in March; the gap between the two grew to six-tenths of a point, an increase, like the month prior, of one-tenth of a percentage point. Unless Edge stumbles badly, it looks like it now has solid lock on second place.

Although Firefox remained flat, Computerworld‘s new forecast – based on the browser’s 12-month average – continued to anticipate a future decline. By that prognosis, Firefox will slide below 7% in July and end the year at 5.9%. That dismal prediction may not come true, of course; in fact, Firefox’s losses over the past six months has been just 40% of that over the last 12, hinting that its decline has slowed.

Mozilla has to be scratching its head, wondering what it has to do to get users on board. In many ways, it’s been the force behind browsers’ emphasis on user privacy, a movement nearly all have gotten behind. Yet it struggles to keep what audience it has, much less grow that.

Edge’s gains make case for Chromiumization

Microsoft’s two browsers – the reworked Edge and run-down IE – combined forces to lose seven-tenths of a percentage point in May, posting a share of 12.5% at its end.

All of that was due to IE, as Edge added a tenth of a point to its total in May, reaching 7.9%, a record for the just-overhauled browser. Meanwhile, IE surrendered eight-tenths of a percentage point, the most since January, to drag its share to 4.6%, the first time that browser has dipped under the 5% mark in the 15 years for which Computerworld has records of Net Applications’ numbers.

While IE’s current share of under 5% may be an undercount – Computerworld remains convinced that metrics vendors like Net Applications have little insight into enterprises, where a single IP external address may mask many internal IP addresses – it’s difficult to know just exactly where the ancient browser stands. It’s clear Microsoft believes it important enough to cater to – seen in the IE mode baked into the Chromium-based Edge – but whether that’s because of popularity inside corporations or just the power of some few very important customers cannot be judged from outside Redmond.

Computerworld‘s latest forecast has IE’s share evaporating to 1.5% in less than a year, which seems unlikely at first glance. Yet the browser, for all its agelessness, will vanish at some point.

Edge’s May was the six straight month of increases, and with 1.95 points added to it during that time, its largest gain since the first half of 2016 when the browser was nearly brand new. From the limited data available – since the end of January, Edge climbed by a less-than-stellar eight-tenths of a point – it appears that the “Chromiumization” of Edge has, at the least, legitimized that browser (where before it was little more than laughingstock). At its current 12-month average growth rate, Edge would be in double digits – specifically, approximately 10.3% – by this time next year.

It would be a mistake to see that as small potatoes, since no browser other than Chrome currently can boast of a double-digit share.

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ data, both Apple’s Safari and Opera software’s Opera remained flat, ending May at 3.9% and 1.1%, respectively.

Net Applications calculates share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers used to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm counts visitor sessions to measure browser activity.

Top web browsers, April 2020

Firefox staved off another ruinous month by remaining stable in April, while Chrome raised its share to a level last seen more than a decade ago by Microsoft’s now largely irrelevant Internet Explorer (IE).

According to data posted Friday by analytics vendor Net Applications, Firefox’s share in April rose very slightly — by less than one-tenth of a percentage point — to 7.3%. It was the first month in the last four in which the browser added share — and more importantly — kept it from dropping below the 7% bar, the milestone not seen since 2005, when Firefox was scratching share from Microsoft’s IE and Google was more than three years away from introducing Chrome.

Firefox remained behind Edge for the second month in a row after ceding second place to Microsoft’s newest browser in March. The gap between them expanded in April by one-tenth of a percentage point to half a point.

Because Firefox remained more or less flat rather than decline as anticipated, Computerworld‘s new forecast — based on the browser’s 12-month average — puts it right at 7% rather than under it at this month’s end. The losses could resume, of course, in which case if they matched the last year’s average, would drop Firefox under 6% by October and leave it at a very dismal 5.3% by year’s end.

Chrome sets record

Chrome climbed by seven-tenths of a percentage point in April, about half what it gained the month before, but it established a record for Google by reaching 69.2%. It was the first time the browser had topped 68% — as it did in March — without slumping the very next month to fall below that level.

In the last 12 months, Chrome has added 3.5 percentage points to its total, the largest change, positive or negative, of any browser during the stretch.

The boost improved Chrome’s 12-month forecast yet again, putting the browser on a linear path of significant growth, considering its dominance of the space. Computerworld‘s prediction now pegs Chrome at above 70% by July and over 71% by November. Only two browsers have accounted for 70% or more of all browser activity since the web’s start: Netscape Navigator (an ancestor of Firefox) and IE. Chrome would join a very selective club.

The last time a browser controlled as much share as Chrome did in April was February 2009, when IE had 69.2%. (The most popular version of IE at the time? IE7, although its lead over IE6 was slim, just a couple of points.)

But can Chrome keep it up? Possibly.

Unlike in 2009, when IE faced a significant rival — Firefox, with approximately 22% of the space — as well as a trio of smaller competitors (Chrome, Apple’s Safari and Opera Software’s Opera), today Chrome’s adversaries are individually weak, none with more than 8%. The way Firefox seems to be headed and the continued inevitable decline and ultimate demise of IE, leaves open more percentage points Chrome may scoop up down the line.

Realistically, the only danger to Chrome anytime soon will be Microsoft’s Edge, ironically a near-clone of Google’s browser.

Edge up, IE down

Microsoft’s browsers, the aged IE and rebuilt Edge, combined to lose three-tenths of a percentage point in April, ending the month at 13.2%.

Edge, though, remained the second-most-used browser last month by gaining two-tenths of a point, reaching 7.8%. Meanwhile, IE gave up four-tenths of a percentage point, sliding to 5.5%. Edge’s number was a record high; IE’s was a record low for the 15 years Computerworld has records from Net Applications.

The Edge-up, IE-down trend has been well established. Though IE’s downhill run has been rapid — it’s lost three percentage points in the last 12 months — that may not reflect the old browser’s residual strength: Browser metrics vendors have a hard time collecting accurate data from enterprise networks, which may mask multiple internal IP addresses by showing a single address externally.

Edge’s April addition was the fifth consecutive month of gains, the most since the first 15 months after the browser’s mid-2015 kick-off when it grew because of Windows 10’s free-upgrade-fueled adoption. Computerworld remained reluctant to call the “Chromiumization” of Edge a success — more data’s required — but the seven-tenths of a point in the last three months, the period since Microsoft released a stable build of the browser, certainly puts it on the path toward the major milestone of 10%.

Ultimately, the only way for Edge to grow beyond that will be at Chrome’s expense. That’s a lot to ask of a browser which is, after all, Chrome at its roots.

Elsewhere in Net Application’s numbers, Safari retrieved the three-tenths of a point it lost the month before, getting back to 3.9%, and Opera Software’s Opera lost less than a tenth of a point to stay, with rounding, at 1.1%.

Net Applications calculates share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers used to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm counts visitor sessions to measure browser activity.

Top web browsers, March 2020

Firefox in March continued a march toward ruin, falling twice its average loss over the past year and losing its place as the world’s second-most-used browser.

According to data posted today by analytics company Net Applications, Firefox’s share in March slumped to 7.2%, down four-tenths of a percentage point. It was the fifth month in the last six in which the browser shed users — and much more importantly — a record low since Firefox climbed out of obscurity to threaten Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (IE) 15 years ago.

This record was the second in a row for Firefox, after February’s debut below the 2016 slump that previously marked the browser’s trough. Two do not a dataset make, but if a legitimate trend develops with, say, another month or two of declines, Mozilla will be, to say the least, in deep trouble.

Notably, Firefox’s fall meant it ceded second place to Microsoft’s Edge. Although Mozilla’s browser had handed second place to Chrome in March 2014 as the latter climbed ahead in the race against the still-dominant IE, Firefox resumed the silver spot in December 2018 when Microsoft’s browser lost it for good.

Computerworld again has had to adjust its forecast based on the latest losses. A month ago, that prediction — based on Firefox’s 12-month average — signaled the browser would fall under 7% in June; now, that mark should be reached in the first few days of May. By year’s end, Firefox’s share could be as low as 5.6%.

Now No. 2, Edge

Microsoft’s browsers — IE and Edge — lost three-tenths of a percentage point in March to end at 13.5%.

But as has been the case recently, the Redmond, Wash. company’s two browsers forged different paths, with Edge rising and IE falling. IE shed half a percentage point last month, plunging to 5.9%, while Edge added two-tenths of a point, climbing to 7.6%, another record high for the five-year-old browser.

Edge’s increase was the fourth consecutive, matching the longest stretch yet of that browser’s gains. In the last two months, Edge has added nearly six-tenths of a percentage point to its total, which represented a growth rate of 8%.

That two-month span was not randomly selected; February and March were the first two complete months after Microsoft released a stable, polished version of the revamped Edge — built atop Chromium code, the same that powers Chrome — on Jan. 15.

Yet the cause of that increase remains unknown. It may be that Microsoft’s decision to clone Chrome is behind the increase, but it is far from certain. More data is needed.

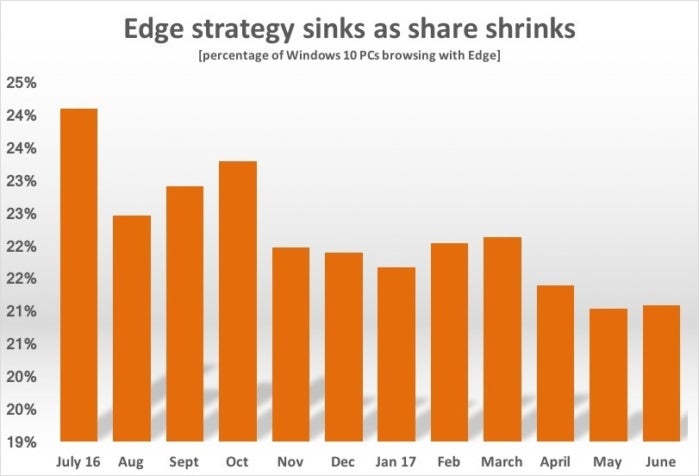

There was a positive-for-Microsoft signal, however. March’s percentage of Windows 10 PCs running Edge — assuming that Edge on Windows 7 and macOS has added little to the total — was 13.2%, tying the record previously set by the browser several times since its introduction. The growth on Windows 10 may be from the beginnings of Microsoft’s automatic swap of old-Edge for new-Edge, even though the firm promised it would not make the latter the default on systems where it wasn’t already set so.

IE’s downturn, meanwhile, was also a positive for anyone rooting for Windows. The browser — in this case IE11, last of its kind — is on what appears to be its deathbed, now under 6% and by all rights should slide under 5% by the end of July. Getting rid of IE — along with its ancient technologies and security vulnerabilities — will be a win for everyone, even if that means shifting legacy labors from that browser to the IE mode inside Edge.

Chrome jumps, again

Chrome leaped 1.2 percentage points last month — the most since September — to reach 68.5%, the highest mark since July, when the browser peaked at a tenth of a point higher.

The increase improved Chrome’s 12-month forecast, putting the browser on a slow river of growth: The prediction now pegs Chrome at around 69% by the end of this year. Computerworld wouldn’t be surprised if that didn’t pan out, however, as the two times Chrome crested 68%, both because of 1.2-point or larger increases, it immediately slumped, albeit not by as much, the month following.

Elsewhere, Apple’s Safari slipped three-tenths of a point to 3.6%, and Opera Software’s Opera remained flat at 1.1%. Safari’s impressive growth of last year, estimates that were flawed because Net Applications counted iPads running iPadOS 13 as macOS devices, was erased from the record when the metrics vendor revised several months of data. By March, Safari had settled into a dead tie with its year-ago number. All the fuss, then, had been for naught.

Net Applications calculates share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers used to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm counts visitor sessions to measure browser activity.

Have work-at-home, stay-at-home orders impacted the browser shares?

To answer that question: Who knows at the moment? But the general drift of the browser shares does hint at an affirmative.

The downturn in Firefox’s fate, for example, makes sense, as it’s the least likely of the top three — Chrome, Edge and Firefox — to be favored by IT. Sent home to work with company devices or told after that to download the preferred browser to their personal PCs to, say, access corporate assets, Firefox may have been replaced in many instances, if only temporarily, by Chrome or Edge.

Meanwhile, Chrome, and to a lesser extent Edge, might have received usage boosts based on the same conceit, that commercially-approved browsers — and both those would certainly apply — would benefit from a mass work-at-home order as has happened in large swaths of the U.S. and elsewhere.

An April of continued gains by Chrome and Edge — and a concurrent loss by Firefox — might confirm the theory, since few companies, at least in the U.S. asked employees to work at home all that month. (Microsoft and Google, for example, ordered theirs home in the first week of March.)

If the COVID-19 pandemic did spark a browser usage shift, will that become permanent? Too soon to know.

Top web browsers, February 2020

Firefox took a significant turn for the worse last month, falling three times its average share loss over the past year and dropping to a level not seen since 2005.

According to data published Sunday by web metrics vendor Net Applications, Firefox’s share in February sank to 7.6%, down six-tenths of a percentage point. It was the eighth month in the last 12 in which Firefox spilled users and the third largest downturn during that stretch.

The last time Firefox recorded a share that low was in September 2005, when it also posted a 7.6% marker. At the time, Firefox was still chipping away at Internet Explorer (IE), Microsoft’s then-keystone of browsers, as it slowly grew to become a legitimate threat to Redmond. IE accounted for an astounding 86.8% of global share in September 2005.

Firefox’s decline erased nearly 7% of the browser’s position at the start of the month. To put that into context, Firefox’s slide was equivalent to Google Chrome’s losing 4.5 percentage points since Feb. 1.

The plummet upended Computerworld‘s forecast, which relied on Firefox’s 12-month average. A month ago, that prediction pointed to a June share of 7.7%. Not only did Firefox lose all that, and more, in just a month but according to the revised forecast, June now looks to be when the browser slips under 7%. By year’s end, Firefox could be as low as 6% unless something clots the bleeding.

The stress of these share losses was recently revealed, as Mozilla posted a revenue-expense imbalance in 2018 and a little later laid off 70 people.

It’s possible things will become even bleaker at Mozilla.

Getting Edgy?

Microsoft’s two browsers — IE and the revamped-with-Chromium-Edge — added two-tenths of a percentage point in February, a slight rebound from the triple-that decline of the month before. IE+Edge ended last month at 13.8%.

The increase, such as it was, came solely from Edge: IE spilled two-tenths of a point, sliding to 6.4% while Edge put four-tenths more on its tally, climbing to 7.4%. That’s as it should be, the old out and the new in.

Edge’s increase put it at a record level, something that’s occurred monthly for the past three quarters. But it’s still impossible to say with certainty that Microsoft’s decision to abandon its own Edge technologies and replace them with those from Chromium has been behind the gradual increase. It is looking increasingly likely, however. February’s percentage of Windows 10 PCs running Edge — assuming that Edge on Windows 7 and macOS contributions has been negligible — was 12.9%, above the 12-month-prior median by a full point.

Meanwhile, IE’s share was at its lowest since September, when it took a temporary dip.

Forecasting Edge’s future will be difficult until it establishes a clearer trend, which may not happen until Windows 10’s growth slows. (Up to Jan. 15, when Chromium Edge officially launched, Microsoft’s newer browser was Windows 10-only; it almost certainly will remain Windows 10-dominant.) Microsoft has promised that it will not make the new Edge the default browser on systems where it wasn’t already so set. That means the company’s plan to replace the original Edge with the Chromium-based Edge shouldn’t artificially boost the browser’s numbers.

Staying Chromey

Chrome added three-tenths of a percentage point last month — the same as in January — to end at 67.3%, its highest mark since October.

The increase left Chrome short of its 2019 peak — 68.6% in July — and improved the 12-month forecast by putting Google’s browser back on a growth road, albeit a very slow road. (The forecast had Chrome staying within 67% through year’s end, even past the midway point of 2021.)

In plainer terms, Chrome will continue to play the browser gorilla. Unless Microsoft pulls some unknown-as-yet rabbit from its Edge hat, Chrome will remain untouched by rivals for the near-to-mid-range future.

Elsewhere, Apple’s Safari slumped four-tenths of a percentage point to 3.9%, while Opera Software’s namesake dropped two-tenths of a point, falling to 1.2%. Safari’s once impressive growth by Net Applications’ account — spurred by mistakenly tallying iPads running iPadOS 13 as macOS devices — was reined in last month when the analytics company revised several months of past data. In February, Safari did stay above the same month’s 2019 level, though (but by just two-tenths of a point).

Net Applications calculates share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers used to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm counts visitor sessions to measure browser activity.

Top web browsers, January 2020

After three months of gains, in January Microsoft’s browsers flipped to the “Decline” setting and shed user share. And for the first time, Microsoft’s newer browser, Edge, posted a larger share than the aged veteran Internet Explorer (IE).

According to data published Saturday by analytics company Net Applications, Microsoft’s January browser share — a combination of Edge and IE — fell by six-tenths of a percentage point to 13.6%. On its own IE dropped almost nine-tenths of a point — that browser’s largest one-month decline since September 2019 — but Edge’s increase of three-tenths of a percentage point nullified some of the older browser’s loss.

For January, IE recorded a user share of 6.6%, while Edge posted 7%. It was the first time since Edge’s mid-2015 debut in its original form that that browser bested IE. (Microsoft relaunched Edge on Jan. 15 as a browser built atop Chromium, the Google-led open-source project whose technologies also power Chrome.)

Although IE might again occasionally edge Edge in user share, the trend will almost certainly be IE’s continued decline. The browser will be supported on Windows 7 for three years and Windows 10 for likely as long, but it’s a dead end kept alive only to keep enterprise customers from revolting. Even Edge’s integrated “IE mode” will eventually be retired.

Meanwhile, Edge’s portion of Windows 10’s browser activity — a measurement Computerworld has touted as a better indicator of the browser’s mettle than user share on all personal computers — ended January at 12.3%, the same number as the month before, hinting that there was little new demand for the revamped Chromium-based Edge on Windows 10, or the other platforms (Windows 7, Windows 8.1, macOS) that it runs on, for that matter.

Edge’s user share performance will be worth watching in 2020, as Microsoft has staked everything on the all-Chromium clone of Chrome, what with IE relegated to a legacy role and the original Edge a complete flop. Going for the new Edge: Microsoft’s reputation in supporting its software in the enterprise, primarily through its management chops. Against it: Chrome’s dominance in corporations, unequal management be damned, and strangely enough, Microsoft’s odd decision to force Chrome in Office 365 environments to default to Bing as its search engine.

If Microsoft perseveres — resistance has mounted, with users and IT administrators denouncing the decision — and weds Chrome to Microsoft Search for Office 365 tenants, it’s annulling one of the most obvious reasons enterprises would adopt Edge.

That just seems odd.

Firefox slumps to share low not seen since 2016

In January, Firefox gave up two-tenths of a percentage point of user share, sliding to 8.1%, the lowest mark since August 2016.

Last month was the eighth straight that Firefox’s user share was lower than 9 percentage points, also a record. (Firefox had a four-month slump in the summer of 2016, but it bounced back, climbing to 13% before it again started the decline that continues.)

Nor is the forecast anything but depressing for Mozilla. That prediction — based, as always, on the 12-month average of changes — now has Firefox slipping under 8% as early as April and falling to 7% by September. Both dates are sooner than the forecast of a month ago because of the January dip.

That’s the last thing Mozilla needs at the moment. It’s 2018 finances showed slightly greater expenditures than income. More recently, the organization admitted it had failed to make its revenue goals, which had included significant subscription moneys, and laid off 70 employees.

Firefox-related subscriptions can’t save Mozilla if Firefox has fewer and fewer users.

Can anything unseat Chrome?

Chrome turned it around — somewhat — in January, adding three-tenths of a point to its user share to end the month at 66.9%. (Ironically, that was the same number Chrome hit in February 2019.)

The small gain put an end to a three-month stretch of losses, a first for Chrome. It also softened the impact of Chrome’s 12-month downturn so that Computerworld‘s forecast now predicts the browser stays about 66% well through this year and all of next. Without considerably more turbulence in Chrome’s share movement, there’s no chance Google loses its top-of-the-heap spot.

Considering the weakness of Firefox, the only viable threat to Chrome has to be Edge, Microsoft’s attempt to supplant the leader with, well, the leader’s step-sister.

Safari’s explosive growth? Yeah, that didn’t happen

And here we thought that Apple’s Safari was making a huge comeback on the Mac. Not so, said Net Applications.

“Due to changes made to the user agent in iPadOS 13, iPads were identified as macOS devices,” the California metrics vendor wrote on its website. “This change propagated progressively from September to December and required an adjustment to the data in that timeframe.”

In other words, by mistakenly tallying iPads running iPadOS 13, which launched in September, as macOS-powered devices, Net Applications overestimated not only the share of macOS but also of anything running on it, like Safari.

In Safari’s case, the differences between the contemporaneous shares and those recently adjusted to remove the iPadOS data were dramatic. In December, for instance, Net Applications had pegged Safari’s user share as 6%.That month’s adjusted share: just 3.8%.

The other months from September on showed similar variance between original and adjusted shares. November’s 5.3% (reported at the time) fell to 3.6% (adjusted by eliminating iPadOS); October’s 4.8% became 3.4%; and September’s 4.4% sunk to 3.4%.

In January, Safari added another five-tenths of a percentage point to climb to 4.2%, meaning that during 2019 Safari grew by less than one-tenth of a point, not the gargantuan-in-comparison 2.3 percentage points Computerworld reported a month ago.

Frankly, the very large gains by Safari should have raised eyebrows and questions. Instead, Computerworld posited that Safari’s growth “demonstrated that Chrome can be vulnerable, at least in some spaces.”

How naive.

Net Applications calculates user share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers people run to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm tallies visitor sessions to measure browser activity.

Top web browsers, December 2019

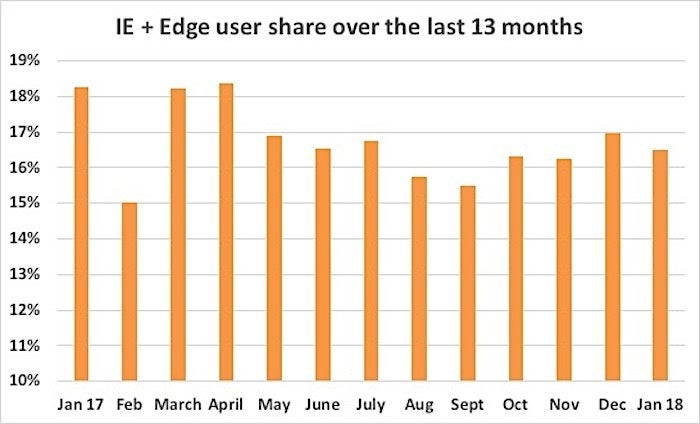

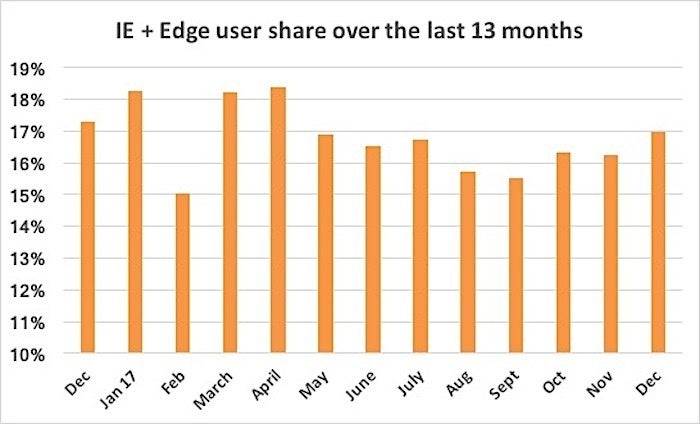

Microsoft’s browsers last month surged to close the year with the highest user share since August 2018, giving its maker a morale boost just weeks before it is to deliver a totally revamped Edge.

According to data published Wednesday by metrics vendor Net Applications, Microsoft’s December browser share — a combination of Internet Explorer (IE) and Edge — climbed 1.4 percentage points to 14.2%, the highest mark in all of 2019. The year’s total user share increase of 1.8 points marked the first time since 2014 that Microsoft’s browsers put in a positive January-to-December.

Over half of December’s gain came from Edge, which added eight-tenths of a percentage point, reaching 6.8%, a record for a browser Microsoft will relaunch in two weeks. IE also climbed last month, adding six-tenths of a percentage point and rising to 7.4%, the most for that browser since August.

(On Jan. 15, Microsoft will begin replacing the homegrown version of Edge on Windows 10 with the new browser built on Google’s technologies.)

Edge’s increase bettered, proportionally, the accompanying December increase of Windows 10, and so the percentage of the latter’s users relying on the browser ticked up to 12.3%, the best number since last summer. December may be the last month that Edge’s portion of Windows 10’s browser activity can be reliably pegged, what with the impending launch of the final “full-Chromium” version for Windows 7, which at the end of 2019 accounted for nearly 31% of all Windows. Although Windows 7 will receive its final security updates on Jan. 14 – except for businesses that pay Microsoft for the post-retirement Extended Security Updates, or ESU — there will be a sizable number of PCs globally running the OS after that date (an estimated 446 million, give or take). It’s almost certain that some will dump IE for the new Edge.

But how much ground the new, Chromium-based Edge gains, if any, once it is in polished form remains unclear. Much will depend on how strong users’ ties are to Chrome, whether IT admins will return their charges to Microsoft’s browser and Google’s reactions. How Edge plays out during 2020 will be among the year’s more interesting enterprise stories.

IE fared well, too, as difficult to believe as that is. By Net Applications’ numbers, IE accounted for 8.6% of all Windows browsing last month, its best mark since May. Although Microsoft has maintained IE on life-support, catering to those organizations that still need it to run specific web apps or intranet sites not worth refreshing, the browser’s share will likely fall as the new Edge’s rises: The remade Edge includes an IE mode, which should make the stand-alone Internet Explorer moot for most commercial customers. Another year like that and IE will be an afterthought run by fewer than 5% of Windows users.

It may be months, however, before an accelerated IE decline, if one occurs, becomes clear enough to fuel future forecasts of its final days.

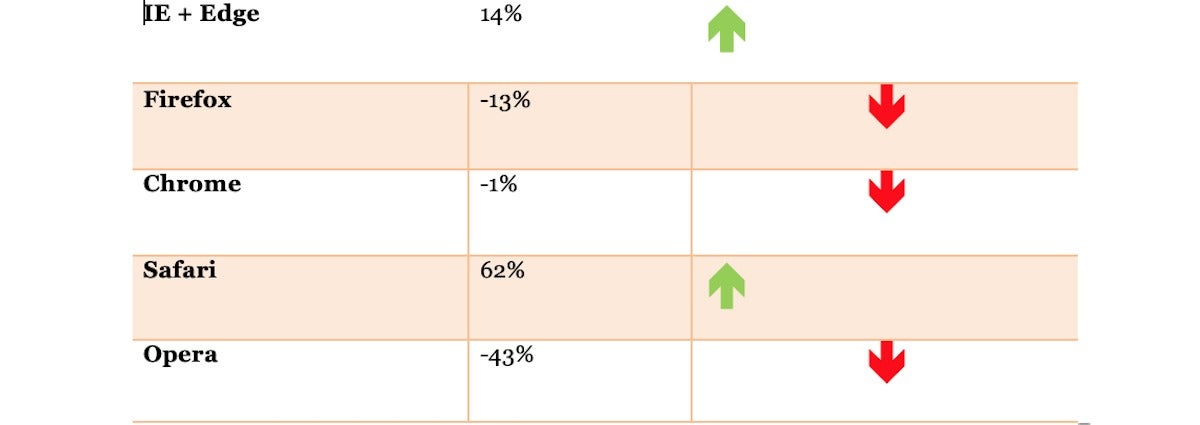

Year-end recap: Microsoft’s browsers gained 1.8 percentage points in 2019, representing a 14% increase in share.

The S.S. Firefox stays afloat

In December, Firefox recovered almost half the user share it lost the month prior; the browser ended the year at 8.4%, up two-tenths of a point from November.

Although that kept Mozilla’s ship from slipping under the waves — something Computerworld feared was in the cards a month ago — Firefox’s future remained more gloomy than glad. It spent the whole second half of 2019 under 9% — the six-month average was 8.5% — and all but one month of the year in single digits, a first (at least since when it was regularly gaining share as it nibbled at IE).

Computerworld‘s revised forecast — based, as usual, on the 12-month average of changes — now has Firefox slipping under 8% by April and falling to 7% about a year from now. And that’s in the face of a small bump in December. The harder Mozilla works, it seems, at improving Firefox — it’s easily the leader in the across-the-browser-market-bar-Chrome anti-tracking movement — the lower droops its user share. How depressing for its fans, users or not.

Year-end recap: Firefox lost 1.2 percentage points during 2019, representing a 13% decline in share.

Chrome sets consecutive loss record

During December, Chrome dropped half a percentage point, slipping to 66.6% and ending the year down that same amount from 2019’s beginning. This was the first time since 2014 that Chrome lost share over the course of a year.

Last month also marked the first time Chrome had posted three consecutive months of losses (they totaled 1.8 percentage points), an even stronger signal than in November that Google’s browser may have topped out.

There’s certainly no danger that Chrome will suddenly find itself usurped by, say, Firefox or Edge, not when it accounted for two-thirds of global browser activity on personal computers last month. But it was impossible for Chrome’s growth, which started seriously only in 2014, seven years after the browser’s debut, to continue forever. Although it may be too early to say Chrome has peaked — the high-water mark thus far was 68.6% in July — declines over multiple months seem a worthwhile indicator.

This year’s browser story should be the impact, if any, on Chrome from Microsoft’s decision to recast Edge as a clone of the Google application. If swaths of enterprise IT decide to ditch Chrome and replace it with the Edge knock-off — for manageability reasons, Chrome could be threatened in the very long term. That has to be at the center of Microsoft’s strategy.

A new Computerworld forecast now puts Chrome on a very gradual — half a percentage point a month — decline, with the browser dipping under 66% sometime in the spring of 2021.

Year-end recap: Chrome lost half a percentage point in 2019, representing a 1% decline in share.

Safari reclaims defectors

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ data, Apple’s Safari posted the fifth straight month of gains, adding seven-tenths of a percentage point to reach 6% in December. Opera Software’s browser lost three-tenths of a point and slid to 1%.

Safari’s increase came as macOS itself dipped to accounting for 11.1% of all desktop operating systems, a decline of half a point from November. In turn, that sent Safari’s share of macOS for December soaring to 54.3%, its highest portion of that market since November 2017. (December was also the third straight month during which that metric increased.) Safari, which has also emphasized its privacy chops, particularly its anti-tracking capabilities, has demonstrated that Chrome can be vulnerable, at least in some spaces; as recently as May 2019, Safari accounted for just 35% of macOS-based browsing.

Year-end recap: Safari gained 2.3 percentage points during 2019, representing a 62% increase in share.

Year-end recap: Opera lost seven-tenths of a percentage points during 2019, representing a 43% decline in share.

Safari boosted its user share by more than 60%, making Apple’s browser the clear winner of 2019. Meanwhile, Opera and Firefox lost ground between January and December. (Data: Net Applications.)

Top web browsers, November 2019

If Firefox were a ship, it would be becalmed on a flat sea, loosened seams leaking faster than the hand-worked pumps can empty the bilge, passengers springing overboard and swimming toward other vessels — those with sails bearing rivals’ logos.

According to data published Sunday by analytics company Net Applications, Firefox’s share for November slumped to 8.2%, down half a percentage point. It was the seventh month in the last 12 in which Firefox spilled share, the fifth where the loss amounted to a half point or more.

From 2005, when Firefox was scratching its way out of the single digits in an insurrection against Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (IE), the browser has posted lower shares only three times, all in a short stretch of 2016 when Firefox bottomed out at 7.7%. That time, the browser clawed back to 13% (in October 2017) before again shrinking.

Unless something suddenly stems Firefox’s current free-fall, the browser will return to that low point of 7.7% by June, according to Computerworld‘s forecast, which relies on Firefox’s 12-month average. That same forecast predicts the open-source browser will dip under 8% as early as January.

Mozilla’s efforts to make Firefox more attractive as a browser choice have failed to move the share needle. From its November 2017 “Quantum” relaunch to its recent emphasis on the hottest browser topic — privacy in general, blocking ad and site trackers more specifically — the improvements and enhancements have been accompanied by collective shrug. Or worse, a step toward the exit.

Historically, Firefox has been the counterweight to the then-current leader, first IE, then Google’s Chrome. Firefox’s flirtation with irrelevancy as exhibited by its smaller user share may see that counterweight go weightless. Microsoft’s decision to adopt Google’s browser technology for its reborn Edge strengthened the monoculture. Sans Firefox, the browser choice becomes Chrome or near-Chrome.

Chrome: Settling into its spot?

During November, Chrome lost a quarter of a percentage point, dipping to 67.2%, the browser’s lowest mark since June.

While the loss was little more than a rounding error and could not be considered a threat to Chrome’s dominance by any stretch, Google’s browser may be close to its upper-end limit.

Last month’s share was identical to Chrome’s number at the start of the year, for one, so for all the wild swings — up 2.3 points one month, down 1.7 points the next — it ended where it began. And although Chrome shed three-quarters of a percentage point in the past six months, in the last three the movements were a wash, hinting that changes to share have slowed.

The forecast based on the 12-month average foretold some gains — Chrome should make the 68% mark by June — but the prophesied increase was significantly less than a month ago, when the prediction contended Chrome would hit 70% by mid-2020.

IE edges Edge

Microsoft’s browsers recovered three-tenths of a percentage point in November, the second straight month of share gains (and only the fourth time that’s happened in the last five years). IE+Edge ended November at 12.8%.

That total was tallied of two browsers, IE and Edge, with the increase credited entirely to the ancient and obsolete IE, not the at-least-newer Edge: IE climbed four-tenths of a point to 6.8% while Edge fell a tenth to 6%.

Because Windows 10’s share of all operating systems also declined, Edge remained with an 11.2% share of all Windows 10 browser activity, the level it’s been stuck at for a full quarter.

Measuring Edge against Windows 10 will soon be impossible, as the revamped browser — Microsoft tossed its own technologies and built a new Edge from Google’s Chromium — will reach release status Jan. 15, launching for Windows 7 and 8.1 as well as 10, not to mention macOS.

Whether Edge’s remodel will result in a jolt to its user share is unknown. Microsoft is, if not counting on Edge’s phoenix-rising, eager to put a thumb on the scale to boost the chances; it will automatically replace the original homegrown Edge with the Chromium-based version rather than wait as users do what they do best, stick with the status quo.

Edge may never gain much ground in Net Applications’ measurements. The California metrics vendor best quantifies individuals’ browsing activity, and while Microsoft wouldn’t object if that group dumped Chrome for a Chrome clone, there’s good evidence that the retuned Edge is a corporate play.

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ numbers, Apple’s Safari gained half a percentage point for the fourth consecutive month, climbing to 5.3%, and Opera Software’s browser remained flat at 1.3%. Safari’s increase came as macOS climbed six-tenths of a percentage point to 11.6%, a record for Apple’s operating system. For November, Safari’s share of macOS rose to 45.6%, the highest mark since December 2017, showing that it is possible for a browser to convince customers to ditch Chrome for a browser they’d used before.

Net Applications calculates user share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers that render the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm tallies visitor sessions to measure browser user activity.

Top web browsers, October 2019

Chrome last month continued its seesaw in user share, throwing away most of the gains it had made the month prior while remaining fully in charge of the browser market.

According to data published today by California analytics vendor Net Applications, Chrome’s share for October dropped by 1.1 percentage points to 67.4%. It was the fourth straight time that Chrome shed some of its share the month following an increase of one point or more. In September, Chrome had recorded a boost of 1.3 points.

The up-down has not always resulted in a net gain for each months’ pairings, and when increases have outweighed losses of the month previous, the upside has been small. That’s why over the course of the past 12 months, Chrome has climbed by just one percentage point.

Yet the difference between Chrome, the browser leader, and the next in line — Microsoft’s Double-mint twins of Internet Explorer (IE) and Edge — was 54.9 points, nearer the high end of the 12-month range between 51.7 and 56.5. That metric shows that Chrome’s position is solid. Very solid, in fact.

Computerworld now forecasts that Chrome will return to 68% shortly (within three months at the most) and crack 70% by June. Even if its seesaw keeps at it.

Firefox slips

One of the unanswered questions in Browser Land is whether Mozilla’s Firefox can survive. Can the browser, which kicked off renewed competition in the space — when it launched in 2004, Microsoft’s IE had eradicated all rivals — keep its head above the proverbial water, say, above the very-minor-browser marker of 5%?

Good question.

Firefox lost one-tenth of a percentage point during October, ending the month at 8.6%. Although that wasn’t Firefox’s nadir of the past 12 months, it was the third-lowest number during that period and the sixth-lowest overall (or at least since the browser crawled out of the single digits in early 2006).

It’s almost painful to watch Firefox struggle to sustain its share, much less grow it. In October, the browser’s user share was below the median for the past 12 months (9.1%) and significantly under the median for the 12-month span before that (November 2017-October 2018, 10.2%).

Although Mozilla continues to stress Firefox’s privacy chops — the latest upgrade added tools that block social media networks’ trackers — that has not resonated enough with potential users to bring large numbers to the browser.

By Net Applications’ data, Firefox’s near future looks weak, but not necessarily bleak. Using the browser’s average movement over the last 12 months, Firefox should remain above 8% for the next year, dipping below that only in November 2020. But if the past six months are a better clue, Firefox is in trouble: That forecast would put the browser under 8% as soon as January, under 7% by June and below 5% as soon as December 2020.

(The difference in the two predictions? The six-month average contains three months of large, more-than-half-a-point losses, which dominated the total. Those three months were diluted in the 12-month average.)

How long will Microsoft maintain IE?

Microsoft’s recovery from September’s all-time browser low wasn’t much of a come-back, but it was better than nothing. In October, the Redmond, Wash. company’s browsers snatched back some of the share they lost the month before, adding four-tenths of a percentage point to up its share balance to almost 12.5%.

The firm’s total was, as always, composed of two different browsers, IE and Edge. And the increase was neatly split between the pair, each adding about two-tenths of a percentage point to the kitty. IE climbed to 6.4%, while Edge edged up to 6.1%.

Windows 10’s share of all operating systems climbed at almost the same rate, so Edge simply kept its share of Windows 10’s browsers at the same 11.2% of September. That mark, remember, was the lowest of the year so far, but not a record low. (The latter would be the 10.9% in September 2018.)

Meanwhile, IE’s increase translated into a slight boost in its share of all Windows browsers, ending October up two-tenths of a point to 7.3%. That IE’s portion of all Windows browsers has fallen by about a fourth — a year-ago, the number was 10.6% — is proof of its fast fade among customers.

Within months, Microsoft will finalize its “full-Chromium” Edge, which will feature an integrated IE mode that replicates that browser for the corporate users who still need it — notably IE’s ActiveX controls — to run aged web apps and obsolescing intranet sites. At some point after the new IE’s debut, Microsoft will forcibly replace the old Edge on Windows 10 PCs (and likely push it onto the Windows 7 systems being serviced by the for-a-free Extended Support Release (ESR) after that OS’s public retirement) with the new.

Computerworld has speculated that Microsoft will eventually purge IE from Windows machines and tell the few customers then still needing the browser to instead rely only on the mode inside Edge. That forecast has been driven by IE’s quickly-declining share. A year from now, going by its performance over the past 12 months, IE will be run by less than 3.5% of all Windows users, just not enough to warrant a separate application.

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ data, Apple’s Safari gained half a percentage point for the second consecutive month, climbing to 4.8%, and Opera Software’s browser stayed dropped a tad to 1.3%. Safari’s increase came in the face of a dip in macOS, which lost about six-tenths of a percentage point in October. That drop in macOS — expected as it was because September’s nearly-two percentage point leap was clearly not realistic — contributed to pushing Safari’s share of Apple’s operating system to 43.9%, the highest it’s been since March 2018.

Net Applications calculates user share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers people use to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm tallies visitor sessions to measure browser user activity.

Top web browsers, September 2019

Microsoft’s browsers stumbled last month, dropping share like a lame Netflix series and falling to a record low after wiping out all of 2019’s gains, plus more.

According to data published today by analytics company Net Applications, Microsoft’s browser share for September — composed of Internet Explorer (IE) and Edge — fell 1.8 percentage points to 12%, an all-time low. To put the decline in perspective, the browsers accounted for a user share of 12.4% at the first of this year and hit a high of 14% in April.

More than two-thirds of that decline was attributed to IE, which plummeted by nearly 1.4 points, falling to 6.1%, a record low for the browser that once lorded if over the web. Edge also slid in September, losing four-tenths of a percentage point and dropping to 5.9%. Edge’s slip erased almost all of its gains in August, when the Windows 10-only browser reached a record high.

Because of the concurrent rise in Windows 10’s share of all operating systems, Edge’s raw decline translated into a more substantial drop in its share of Windows 10’s browsers. That number fell to 11.2% in September, the lowest level all year.

Although the “full-Chromium” Edge, the version Microsoft’s building using technologies from the Google-dominated Chromium project, is under construction, the browser’s future is cloudy at best. Clarity won’t come until Microsoft finishes the Chromium-based Edge and forces that onto Windows 10 users, something the company has said it will do at some point after launch.

IE fared even worse in a comparison with all the other browsers that run on Windows. By Net Applications’ numbers, IE accounted for only 7% of all Windows browsing last month, also a record low. Microsoft kept IE on support only because some organizations require it for aged apps or intranet sites, but that rationale has faded fast: In the last 12 months, IE’s share of all Windows declined by 60%. Another year like that and IE will be an afterthought run by fewer than 5% of Windows users.

Firefox scratches, survives another month

Firefox added three-tenths of a percentage point to its user share in September, wrapping up the month at 8.7% and marking the second straight month of keeping things in the black. Even so, it was fourth consecutive month that Firefox remained under 9%, tying a record set in May, June, July and August 2016.

Although it was another month that Firefox scratched out some gains, the browser still stands on shaky ground. Because the last 12 months shows a decline of nearly a percentage point, Computerworld‘s revised forecast — based on the 12-month average — has Firefox slipping under 8% about mid-2020.

For all of Mozilla’s work on Firefox — from the redesign two years ago to its aggressive adoption of anti-tracking and pro-privacy measures — nothing has kicked the browser into sustained growth. A year ago, Firefox’s share was 9.6%; when Mozilla introduced Firefox Quantum in November 2017, the share was 11.4%. Only three of the past 18 months recorded shares of 10% or more.

Chrome commandeers more share

Google’s Chrome put another 1.3 percentage points on its frame, weighing in for the month at 68.5%, just a tenth of a point off the record high set in July.

Last month, Computerworld noted the odd pattern to Chrome’s share, stretches when the browser would add share one month, lose much of it the next. That continued in September — this has been regular as the proverbial clockwork since February — when Chrome went on its growth spurt after shedding 1.4 points in August.

If the tick-tock continues this month, October should be a downer for Chrome.

But as Computerworld has said before, what counts is the long-term movement of a browser. There, Chrome has done well, adding 2.1 percentage points to its share over the last year. Another sign: The 68.5% of September was the second-highest mark for the browser, edged out only by July’s 68.6%.

Chrome’s gains, stymied as they have been at times by losing months, put a new spin on Computerworld‘s prediction of its future. Using the 12-month average, the forecast pegs Chrome at more than 69% in November and over 70% by May.

Computerworld has Net Application records going back to January 2005, so it’s possible to compare Chrome’s prowess today with IE’s of yesteryear.

Google comes off second best there — for now, at least — because IE’s share was an astounding 89.4% that month. The remainder was split among rivals, including Firefox (at 5.6%), Apple’s Safari (1.7%) and Netscape’s Navigator (2%). It wasn’t until December 2008 that IE’s share fell to about where Chrome’s is now.

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ data, Apple’s Safari grew by half a percentage point to 4.4% and Opera Software’s browser stayed where it was at 1.4%. Safari’s increase was the second straigh,t but was a due entirely to a nearly-two percentage point leap by macOS that put the operating system in unknown territory (and likely on shaky ground; macOS’ 11.6% simply won’t stand up).

Net Applications calculates user share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers people use to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm tallies visitor sessions to measure browser user activity.

Top web browsers, August 2019

Microsoft’s Edge completed a six-month surge in user share that represented a 24% increase and brought the browser to its highest-ever level.

According to U.S. analytics vendor Net Applications, Edge’s August user share rose by half a percentage point to 6.3%, a record for the browser in its first four years. During the six months ending Aug. 31, Edge added 1.6 points to its share, the equivalent of a 24% boost.

The growth by Edge, however, did not translate into a similar-sized increase in the browser’s portion of Windows 10 browsers because the operating system jumped up more than two percentage points. (Although the “full-Chromium” Edge, the version Microsoft’s building using the Google-dominated Chromium project’s technologies, has been released in preview for non-Windows 10 OSes, it’s a certainty that the vast bulk of Edge’s users are on 10.)

By Net Applications’ numbers, Edge accounted for only 12.4% of all Windows 10 browser activity, a half a point increase over the month prior. But the six-month increase of Edge’s share of Windows 10 was a measly 4%.

It may be tempting to credit Microsoft’s switch to Chromium for the increase but Microsoft did not give users a working preview until mid-April. Of the four months since, two recorded decreases in Edge’s browser share.

Until Microsoft rolls out a polished version of full-Chromium Edge — a Stable channel build, using Chrome’s nomenclature, which Microsoft has adopted — and better yet forces the new Edge onto Windows 10 users — Computerworld is convinced it will be impossible to pin the browser’s ups and downs on the revamp.

On the share stairs, Chrome takes one step down after two up

After a near-record leap in July, Chrome last month dropped 1.4 percentage points, falling to 67.2%, the same number it booked at the start of 2019.

Chrome has had a habit of doing this two up, one back — or even two up, two back — recently. In May, Chrome added 2.3 points, then promptly lost 1.6 points in June. July saw an increase of another 2.3 percentage points, with August subtracting 1.4 of those.

The ups and downs have produced projections that have been alternately up- then downbeat. This one is the latter: Chrome now won’t reach the 70% milestone until December 2020, a full year later than the forecast of just last month. (Reality will likely be somewhere in between.) But there’s still no signal that Chrome’s rise has plateaued, much less that it’s in danger or reversing.

Edge’s 1.5 percentage point increase over the last six months notwithstanding, there simply isn’t a competitor worth the name among the browsers-not-named-Chrome.

Firefox hangs on

Firefox added a tenth of a percentage point to its user share in August, wrapping up the month at 8.4% and putting an end to a three-month slide.

But August was also the third consecutive month that Firefox remained under the 9% bar. Its record: Four straight months below 9% in May through August 2016.

While Firefox at least didn’t lose share, it continued to flirt with disaster. Computerworld‘s revised forecast put the browser under 8% by November and predicted that the browser will drop below 7% by August 2020.

It becomes harder and harder to visualize how Mozilla will work its way out of the browser basement. Can its focus on privacy, specifically the emphasis on blocking web trackers, convince millions to try (or retry) Firefox? That seems tough when every rival but Chrome rushes to implement their own anti-tracking. Is the enterprise Firefox’s salvation? How can it be when Microsoft positions Edge as more-or-less-Chrome but with its enterprise imprimatur? Firefox needs a solid six months of growth at a minimum to convince anyone that it has put possible extinction behind it.

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ numbers, Apple’s Safari grew by half a percentage point to 3.9% and Opera Software’s browser slid a tad to 1.4%. The only silver lining for either was Safari’s share of all macOS-powered computers — 39.8% — was the highest since May 2018.

Net Applications calculates user share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers people use to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm tallies visitor sessions to measure browser user activity.

Top browsers, July 2019

Chrome again jumped in user share, adding the most in a single month since its 2016 heyday, when Google took advantage of a disastrous Microsoft decision to claim the top spot.

According to web analytics company Net Applications, Chrome’s July user share climbed by 2.3 percentage points to end the month at 68.6%, a record for Google’s browser. The month’s increase was the largest since August 2016, at the tail end of an eight-month tsunami that swept Microsoft from its decades-old perch.

In five of the past seven months, Chrome has held more than two-thirds of global browser share, a statement to its grip on the market. The only extant browser that has accounted for such a large portion of the world’s web activity? Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (IE), which a decade ago was as dominant as Chrome is today.

But Microsoft deliberately pulled the plug in the IE bathtub and within months watched its lead swirl down a drain. In mid-2014, the Redmond, Wash. company told Windows users that they would have to upgrade to the newest-available IE for the OS running their PCs. The order scratched a year of support from IE7, four years from IE8 and IE9, and seven years from IE10. (At the time, IE8 was the most popular version of the browser.) Only IE11 survived with support intact.

But if Microsoft expected an uptake of IE11, it was sorely disappointed. After the mandate went into effect in January 2016 — when more than half of all those running a Microsoft browser were forced to switch — a stunning decline began. In the first eight months of 2016, Microsoft’s global browser share plummeted 16 percentage points, representing a loss of about a third of its total. During the same stretch, Chrome gained 21.6 percentage points, sprinting from 32% to 54%. Computerworld has long maintained that when faced with an upgrade of one sort or another — IE8 to IE11 or IE to Chrome — millions upon millions picked the latter.

In any case, IE never recovered, and Chrome has never looked back. Instead, Google’s browser has angled to eat the world. According to its 12-month average user share change, Chrome will account for more than 70% of all browser share by the end of the year. By the end of 2020, that number will approach 75%.

Firefox feels like it’s slipping away

Firefox shed user share again in July, making for the third consecutive month of losses. Mozilla’s browser dropped half a percentage point, falling to 8.3%, a mark not far above its record low of 7.7%, which it recorded three years ago.

Although Firefox has had several three-month periods where it lost user share, the 1.9-point total decline of the latest was the largest since a 2.3-point drop between November 2017 and January 2018.

As Computerworld has pointed out before, Firefox has had a tough time the last two years. Every once in a while, the browser posts a positive number, but those gains are always erased. Over the last 15 months, for example, Firefox reached 10% or more just twice, most recently in April. But then May, June and July came and washed Firefox near the 8% bar.

Firefox’s prognosis remains dire. In the last six months, the browser gave up 1.9 percentage points of user share, a depressing amount for an application that has no fat to begin with. Computerworld‘s latest forecast puts Firefox under 8% by October and contends that the browser will flirt with a sub-7% share by July 4, 2020.

Mozilla has banked on privacy as Firefox’s edge over rivals. But it’s also recently trumpeted enterprise manageability, likely hoping for some adoption in organizations apprehensive about Chrome’s connection to Google, and the latter’s reputation as a data collector and monitor of online behavior. Something had better work for Firefox, or it could easily become a boutique browser forever stuck in the low single digits.

Good luck with that Edge thing

Meanwhile, Microsoft’s browsers — IE and Edge — were also down for July.

The combined user share of IE+Edge slipped by one-tenth of a percentage point to 13.2%. Over the past several months, Microsoft’s browsers have alternately climbed and fallen, often taking one step forward followed by two steps back. Over the past six months, for example, Microsoft has added seven-tenths of a point to its user share bank; but during the past 12 months, it was down 2.1 points.

The July downturn was on Edge’s shoulders: Microsoft’s newest browser lost two-tenths of a point, slumping to 5.8%. Only a curious increase in IE by about three-fourths that amount kept Redmond’s losses down. (At this point, how is IE collecting new users?) Amazingly, IE, with a user share of 7.4%, continued to tally more user activity than Edge.

Edge — the current Edge — accounted for just 11.9% of all Windows-based browsing activity, a significant slip from the month prior, caused by Edge going down and Windows 10 going, well, up in spades.

Neither of Microsoft’s browsers are going to set any growth records. In fact, by the IE+Edge 12-month average, they’ll continue to contract. At the end of 2019, the combined user share will have dropped to 12%; a year from now, they could account for just 11% of all share.

Microsoft has its work cut out for it in reclaiming Edge from the morgue.

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ numbers, Apple’s Safari grew by a tiny tad to 3.4% and Opera Software’s eponymous browser slid a small bit to 1.4%. The only silver lining for either was Safari’s share of all macOS-powered personal computers — 37.9% — ending up setting a three-month record.

Net Applications calculates user share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers people use to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm tallies visitor sessions to quantify browser user activity.

Top browsers, June 2019

Mozilla’s Firefox took a user share beating for the second straight month, slipping under 9% for the first time since November 2018.

According to web analytics vendor Net Applications, Firefox’s June user share fell seven-tenths of a percentage point to 8.9%. The month’s decline was the second-most since Net Applications reset shares — to purge bot traffic from its data — more than a year and a half ago. Firefox’s largest one-month decline since then? May’s slide of just over seven-tenths of a point.

As Computerworld pointed out a month ago, Firefox has had a very tough time generating share growth over the last two years. Every once in a while, the browser posts a positive number, but those gains are quickly erased. Over the last 14 months, for example, Firefox recorded a share of 10% or more just twice, most recently in April. But then May and June came along and washed Firefox back under the 9% bar.

Firefox’s long-term prognosis remains dire. In the past year, the browser shed 1.3 percentage points of user share, a depressing amount for an application that has no fat on its frame. Computerworld‘s newest forecast has Firefox slipping below 8% by March 2020, then flirting with a sub-7% share near the end of that year.

But Mozilla’s browser has been in a slightly deeper hole before, then climbed up if not out of that hole. Three years ago, Firefox sank under 8%. Yet in six months, it had added more than four percentage points to its share total. Firefox largely held those gains for the next year before again heading into a downturn. Maybe Mozilla can pull another rabbit from a hat, perhaps on the back of its anti-tracking initiative, which has garnered attention if not users.

More for Microsoft’s Edge

While Mozilla’s browser lost user share, Microsoft’s found some more.

The combined user share of Internet Explorer (IE) and Edge climbed by three-tenths of a percentage point to 13.3%. But the added share did little to change Microsoft’s overall trend, which has been negative for much longer than CEO Satya Nadella has held the company’s top spot: IE + Edge lost 3.1 points in the past 12 months.

The user share drop-off came from IE, the legacy browser Microsoft maintains with monthly security updates but won’t upgrade with new features. Over the last year, IE’s share dropped 4.9 points; meanwhile, Edge added 1.9 percentage points during the same period.

In June, just 8.3% of all Windows users ran IE, a record low for the iconic browser. At its current 12-month average, IE will zero out within two years. That’s unlikely — someone will be running the creaky application in July 2021 — but the projection still speaks a truth, that like the rivals Microsoft crushed, IE will eventually go extinct.

Edge’s user share of all personal computers grew by seven-tenths of a percentage point in June, ending the month at 6%. The latter was a record high for Windows 10’s default browser. Edge accounted for an estimated 13.2% of all Windows 10 browsing activity last month, up 1.5 points from May and that metric’s highest point since April 2018.

It was unclear why Edge’s user share jumped in June, but it was almost certainly not due to the still-under-construction “full-Chromium” Edge, the revamp that will be powered by the same open-source rendering and JavaScript engines as drive Google’s Chrome. Full-Chromium Edge has yet to reach beta status, much less a production-quality stable build, and has been available to Windows 7, Windows 8 or Windows 8.1 for less than two weeks.

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ numbers, Chrome stalled for the second time in three months, losing 1.6 percentage points to drop to a still-overwhelming-user-share-lead of 66.3%. June’s decline was the third largest for Chrome, beaten only by August 2013’s 1.8 points and April 2019’s 2.2 points. The whacky up-down-up-down-up rhythm of Chrome’s short-term moves thus continues.

Even the April and June losses, however, didn’t eliminate the year-long gain by Chrome: Google’s browser added 3.5 percentage points in user share over the past 12 months. June did, though, confuse Chrome’s future. Where the prior prediction pegged the browser making the 70% mark by October, the latest losses postponed that milestone to July 2020, near the prognosis put forward after April.

Apple’s Safari stayed stable in June at 3.3%, its lowest mark since the end of 2008. Safari’s smaller share was yet again partly due to the continued shrinking of macOS, which slipped between one- and two-tenths of a point last month. Just like IE, Edge and Firefox, Safari has been damaged by Chrome’s growth; Safari’s share of all macOS stood at 36.3% in June. Even though that was slightly better than the month prior, it was a shadow of its past. Four years ago, Apple’s browser accounted for two thirds of all Mac browser activity.

Net Applications calculates user share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers people use to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm tallies visitor sessions to quantify browser user activity.

Top browsers, May 2019

Chrome in May bounced back from a massive April decline to reach a record user share of nearly 68%, sending rivals’ shares tumbling.

As Computerworld pointed out a month ago when reporting on Chrome’s record loss during April, short-term browser movements often lead nowhere. Such was the case when Chrome did a 180-degree turn, adding 2.3 percentage points in May, more than it had lost the month before.

The bounce-back was the fourth straight time that, when Chrome lost user share, it regained enough to erase the loss a month later.

According to Internet analytics company Net Applications, Chrome’s May user share reached 67.9%, a new high for the Google browser. The increase was the largest since August 2016, when Chrome accounted for 54% of all user share and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (IE) and Edge still owned over a third of global share. Over the last 12 months, Chrome has gained five percentage points.

May’s gain put Chrome back on track to break the 70% barrier before year’s end. Where last month’s forecast pegged the browser making that mark by June 2020, the latest calculation — based on the 12-month average — pegs Chrome at 70% by October.

Firefox retreats…, again

As Chrome climbed, other browsers descended the user share ladder. Mozilla’s Firefox lost seven-tenths of a percentage point in May, its largest single-month decline since November 2017, when Net Applications reset shares across the board because it eliminated bot-driven traffic from its data. Firefox last month fell to 9.5%, returning the browser to its December 2018 level.

Firefox has had a terrible time sustaining any user share growth. In the last year, the longest uptick has been just two months, so May’s quick retreat wasn’t unexpected. But it has to concern Mozilla that the browser, the mainstay of its efforts, can’t shake itself out of the single-digit doldrums, climb into 10%+ territory and stay there.

Computerworld‘s latest forecast for Firefox now concludes the browser will remain under 10% for the foreseeable future, sliding below 9% in August 2020. Somehow, Mozilla’s engineers and designers have to come up with features that will entice new users to join up (or old ones to return). The November 2017 release of “Quantum,” a Firefox redesign that rolled out to some fanfare, has failed to translate into greater share. In fact, it’s been the opposite: Firefox’s user share has fallen about 2 percentage points since, representing a 20% decline.

Only Microsoft’s browsers have dropped more than that in the same stretch.

IE’s share of all Windows slides below 9%

Elsewhere in Net Applications’ numbers, the combined user share of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (IE) and Edge slid nine-tenths of a percentage point to 13%. The decline added to the ongoing slide for Microsoft’s browsers, which have lost 3 percentage points in the last 12 months. May’s fall erased more than two-thirds of April’s out-of-the-blue gains.

Most of the user share drop-off came from IE, the legacy browser Microsoft maintains with monthly security updates but won’t upgrade with new features. During May, an anemic 8.7% of all Windows users ran IE. No wonder some — including Computerworld — expect IE to vanish, or at best be absorbed into Edge when that browser adds an IE mode to its Chromium foundation.

Edge slipped as well, dipping in May by two-tenths of a percentage point, even as Windows 10’s user share grew by 1.6 points. Edge accounted for an estimated 11.7% of all Windows 10 browsing activity last month, down eight-tenths of a point from April. That was, however, the first decline since December.

Apple’s Safari fell three-tenths of a point — three times what it had lost in April — to end at 3.3%, its lowest since the end of 2008. Safari’s smaller share was again at least partly due to the continuing shrinking of macOS user share, which slipped about a tenth of a point. But like IE, Edge and Firefox, Safari has suffered from the come-to-Chrome movement; its share of all macOS drooped to 35.5% in May. Two years ago, Apple’s browser owned 54% of the Mac browser activity market.

Net Applications calculates user share by detecting the agent strings of the browsers people use to reach the websites of Net Applications’ clients. The firm tallies visitor sessions to quantify browser user activity.

Top browsers, April 2019

Chrome last month lost a record amount of user share, a measurement of browser activity, just one month after reaching a new all-time high.

Down. Up. Up. Down. Tracking the month-by-month movement of browsers’ user share can be trying when the data doesn’t show a crystal-clear short-term trend line. Does this mean that Chrome is poised to plummet? Doubtful. Could it? Certainly. Nothing stays on top forever.

Just ask Microsoft.

According to Internet analytics vendor Net Applications, Chrome’s user share plunged 2.2 percentage points in April to 65.6%, its lowest mark since October. The fall was over half a point more than the previous record, set in August 2013, when Chrome accounted for a mere 16% of all user share and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (IE) was the beast of browsers with 57.6%.

Even that massive drop-off, however, didn’t erase the past year’s gains by Google’s browser. For the last 12 months, Chrome remained up four percentage points, the most of any browser by far. History is also in Chrome’s favor: The last three times Chrome lost user share, the following month it added a percentage point or more of share to its total, enough to erase the earlier decline.

The plunge did put a crimp in Chrome’s bid to break the 70% barrier. Where last month’s forecast pegged the browser making that mark by August of this year, the latest calculation — based on the 12-month average — puts 70% down on the calendar for June 2020.

Firefox scratches above 10%

In the zero-sum browser game — one’s losses means another’s gains — Mozilla Firefox was one of April’s winners. The open-source browser gained a full percentage point, ending the month with 10.2%. The total was Firefox’s highest since March 2018 and the first above 10 points since June that year.